The week before my trip to South Korea, a US Senator called North Korea’s Supreme Leader a “crazy fat kid.” The North Korean response: ‘the comment was “a little short of a declaration of war.”’ There was no better time to visit the frontline of this nuclear-armed school-yard conflict.

What is the DMZ?

A map of the DMZ.

(Author: Rishabh Tatiraju licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0).

Before Word War 2 the Korean Peninsula was occupied by the Japanese. When the war ended, the United States and the Soviet Union divided the country roughly in half. In 1948, each region established a government, backed by their respective superpowers. Each government claimed that it was the legitimate government for the whole Korean Peninsula.

In 1950, North Korea, led by Kim Il-Sung and backed by the Soviets, invaded South Korea. The North overran Seoul and most of the Korean peninsula until the United Nations, backed by the United States, Australia and others stepped in.

UN forces re-captured Seoul and most of North Korea. Then the Chinese, fearing US forces on their border, sent forces to assist the North Koreans. UN forces were pushed back until the frontline ended roughly where it all started.

The first page of the Armistice Agreement that stopped open hostilities in the Korean War.

The UN, North Korean and Chinese forces agreed to an Armistice to “suspend open hostilities”. That agreement doesn’t resolve the conflict, so technically, the two Koreas are still at war. The Armistice created the DMZ as a 4-kilometre buffer zone between the opposing armies.

Into the pressure cooker

It was a strange feeling sitting on a tourist bus headed to the frontline of this long-running conflict. On one hand, it’s a very serious affair. But on the other hand, everything is just so bizarre you wonder whether you’ve entered an alternate reality.

It began with the instructions I received for the tour. Amongst other things: No ripped jeans, no oversized clothing or “excessively baggy trousers” and no umbrellas. Why? Because the North has a habit of photographing badly dressed tourists and using that as propaganda to say that the outside world is so poor that they cannot afford proper clothes.

To the depths of the earth

A diagram of the tunnels.

The first stop was the Third Infiltration Tunnel. After the Armistice, the North Koreans dug tunnels under the DMZ to launch a surprise attack on the South. There are believed to be about 20 tunnels, but only four have been found. Comically, the North denied building them, then admitted it, but claimed they were coal mines. There is no coal in the area.

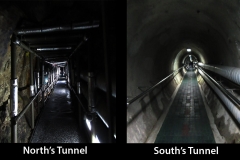

To access the North Korean tunnel, I first walked down an interception tunnel built by the South. And although the North claims their Supreme Leader could drive at age 3 (seriously, he claims that), their tunneling skills are far less divine. The North’s tunnel was cold, damp and not designed for anyone over 5-foot. The South definitely win the prize for best tunnel. They even installed a train for lazy tourists.

The North Korean tunnel is 1.6km long, but after a few hundred meters of bumping my head on the ceiling, I was met with the first of three concrete barriers installed to disable the tunnel. It is an eerie feeling, being 70 meters underground, in a dimly lit and cramped tunnel, looking through a small window into darkness, beyond which is the arbitrary line dividing the Korean people.

The North Korean tunnel is 1.6km long, but after a few hundred meters of bumping my head on the ceiling, I was met with the first of three concrete barriers installed to disable the tunnel. It is an eerie feeling, being 70 meters underground, in a dimly lit and cramped tunnel, looking through a small window into darkness, beyond which is the arbitrary line dividing the Korean people.

Observing the North

The next stop was the Dora Observatory, a vantage point where I could see across the DMZ and into North Korea.

A view over the DMZ into North Korea.

From the North, you can hear loudspeakers blaring propaganda in Korean. The guide told me that they were declaring that the North was very prosperous and were inviting South Koreans to defect.

From the otherwise empty DMZ area were two villages. When the DMZ was declared, the South Korean village of Daeseong-dong was in the zone. Its inhabitants were asked to relocate, but they refused. The result was an agreement that each Korea could have one village inside the DMZ.

The North then built Kijŏng-dong (or as the South prefers: Propaganda Village). Apparently it’s only purpose is to annoy the South and most of its buildings are empty concrete shells for display purposes. In the 1980s, the South built a 98 m flagpole in their DMZ village. In retaliation, the North responded with 160 m flagpole in Kijŏng-dong. So now both villages have ridiculous oversized flags.

The flagpole war.

Life for the inhabitants of the South Korean DMZ village must be difficult. Propaganda from both sides blares across the DMZ at all hours of each day. They are subject to strict curfews and need to apply to the military to have visitors. But it isn’t all bad: they do no pay taxes.

The train to nowhere

Dorasan Station. Despite the sign, the trains do not run to Pyongyang, North Korea.

One piece of infrastructure that apparently didn’t undergo a cost-benefit analysis is Dorasan Station. It’s a train station where you can stand on a platform to board a train to Pyeongyang (the North Korean capital), except you can’t – because trains don’t cross the border. By reality doesn’t stop the optimism of public transport. Apart from its lack of trains (and any real travellers) this is a fully functioning train station, complete with seats, route maps and departure boards.

This station epitomises the weirdness of this conflict. Secret tunnels, an empty village, ghost train stations and huge flagpoles; all to be observed by impeccably dressed tourists (without umbrellas).

3 thoughts on “The Korean Demilitarised Zone: the world’s weirdest frontline”

Comments are closed.